6 May 2018

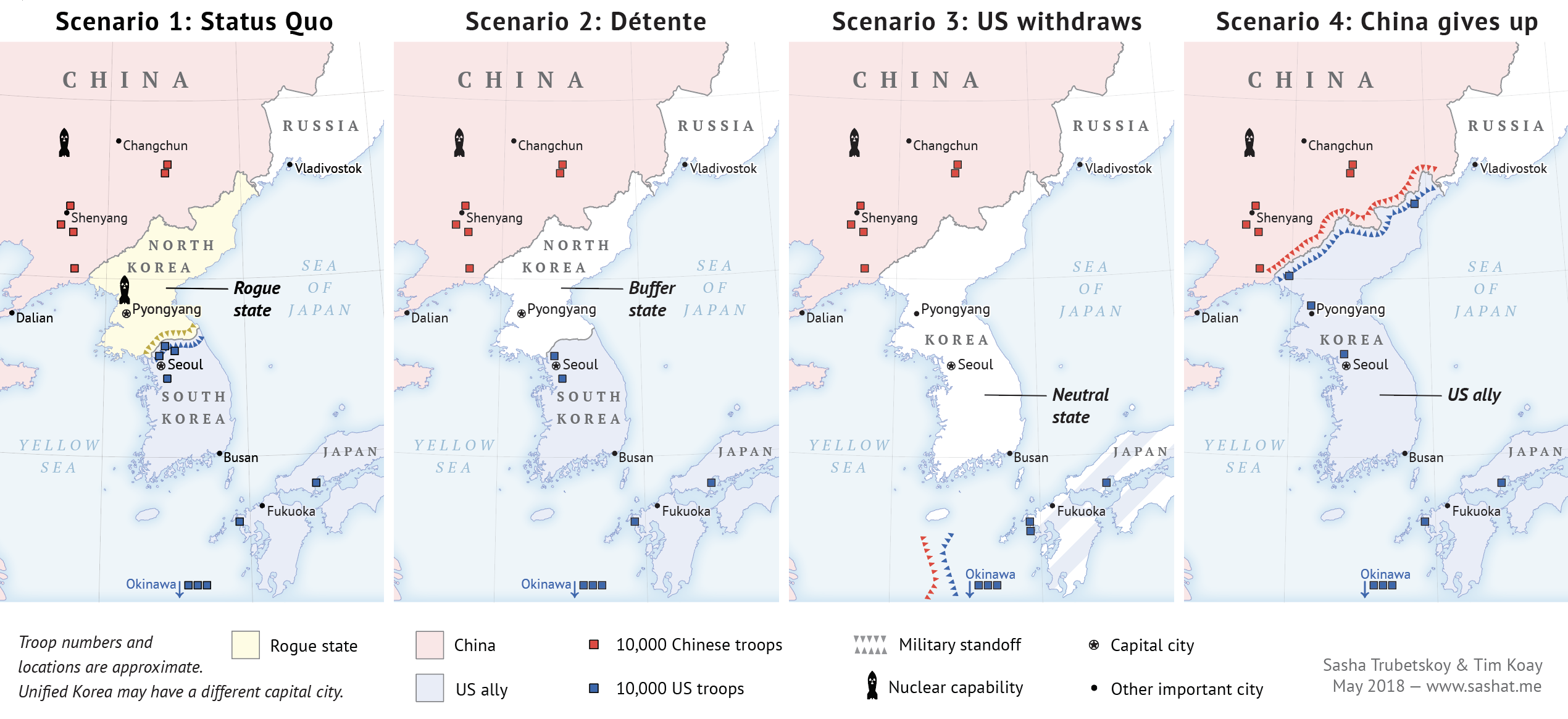

Four possible outcomes in Korea

The Panmunjom Declaration is an exciting step towards peace on the Korean peninsula—a goal many have worked hard towards across many decades. We have forecasted four scenarios of potential developments as a result of future summits, closed-door deliberations, and agreements. A realistic view of current developments would mean that the future most likely lies somewhere between Scenarios 1 and 2.

The summit is an easy political win. The West hears what they wanted to hear, the South Koreans kept campaign promises, and the media has a field day. Yet, for all the excitement of a new generation of peace, stability, and warmer relations, people forget that concrete steps must be taken before any “declaration” becomes reality. Such steps are absent from the most recent joint declaration. The loudspeakers at the border fall silent and the diplomats promise to pursue vague “non-aggression agreements”, but neither side takes tangible strides towards cooperation. Kaesong Industrial Zone remains closed, and the DMZ remains littered with landmines in the absence of a cleanup effort. In the end, this brief period of anticipation was rendered moot just like the previous attempts at reconciliation. The two Koreas retreat back to their well-worn rhetoric, each side blaming the other for failing to advance relations. The two systems simply irreconcilable.

The North Koreans restart their ICBM and nuclear programs, using the threat as leverage to extract concessions from the international community, but never quite willing to push the American-led alliance to any kinetic intervention. Kim Jong Un is too smart to do that. All of his posturing and cleaning house so far helps resolve the age-old predicament of dictators everywhere—ensuring survival. Compelling the Americans to act forcefully would only put that hard work in jeopardy.

The Chinese are fine with the arrangement, since they still largely control the trade routes and commodities that keep the North Korean economy alive—retaining political leverage. Furthermore, not only does Kim remain a constant thorn in the Americans’ side with his nuclear threats, but the status quo means that no American ally borders China’s northern regions. Realpolitik remains the name of the game.

Kim Jong Un realizes that his domestic economic situation is increasingly untenable. He is not steeped in his father’s radical ideology, having been educated in the West and more aware of the systems governing the world. But he is also not willing to renounce power. Kim recognizes an optimal path in the Beijing Consensus—a nominally capitalistic model that allows trade flows to reach North Korean shores and to improve his people’s living standards, while maintaining a centralized power structure. North Korea embraces the system of market capitalism (with North Korean characteristics) first developed by its Chinese patrons and slowly leaves behind its isolationist ways.

By agreeing to suspend their nuclear and missile programs, the North Koreans satisfy Western conditions for the slow roll back of sanctions. Over time, relations with the South inevitably turn for the better. The 2018 diplomatic efforts were not the watershed moment people had hoped for, but they did jump start the bilateral economic flows that resulted in closer ties. As trust builds, both sides begin dismantling the DMZ and preparing to build transportation networks to facilitate the movement of capital. South Korean businesses jump at the opportunity to expand into the North Korean market, tapping into its cheap labor reserves. Reunification remains non-viable—despite North Korea’s move towards integration into the global trade network, Kim is unwilling to give up his position at the top.

As the threat of a Northern invasion dies down, American troop levels decline as well. The United States retains sufficient forces “just in case”, as well as robust intelligence assets to probe into China. The South Koreans regain wartime command duties. Despite warmer North-South relations, militaries on both sides remain wary of each other. The Chinese are happy for North Korea to serve as a buffer against Western forces, as well as a case study that legitimizes Beijing’s economic model. And who knows—perhaps the Koreans would be open to joining the Belt and Road.

The confluence of American isolationist sentiment and the Korean drive for unity results in a merged, neutral Korean state, with the complete withdrawal of American forces.

The two Koreas adopt a single, temporary constitution with a federal structure that maintains Northern and Southern executive power structures in place, pending further integration. National elections are scheduled to elect a head of state, whose role is mostly ceremonial. An entirely new Assembly is also elected, based in Seoul, though many call for a brand-new capital city to be constructed.

Jubilant, patriotic Southerners flood the North with aid after a special federal commission is created to handle distribution. The new government sets up work relief corps to rapidly retrain the Northern population for a modern economy, creating programs to upgrade northern infrastructure. Teachers, social workers and entrepreneurs from the South begin moving into Northern towns and cities. However, travel restrictions remain in place to prevent a Northern migration crisis, to be gradually lifted as integration milestones are achieved.

The US essentially abdicates its say in Korean dynamics, loosening its hold on the Northern Pacific. The Chinese are all too happy to step into the vacuum. The Americans’ departure from the peninsula marks the first time that China is able to push America’s ring of allies back into the Pacific. The PLA Navy continues its blue-water ambitions and moves toward reclaiming its status as the preeminent Pacific power, at the expense of the US Navy.

Japan is left stranded. Chinese influence continues to encroach on Japan’s historical sphere of influence. The Japanese are left with two choices. They can acknowledge China’s status as the preeminent Pacific power, play nice, and retain access to the Chinese markets, attempting to optimize their position within a Sino-centric order. Or they can double down on their military buildup and rise up to check the expansion of Chinese power at the expense of great economic access.

President Trump dusts off his first edition copy of Trump: The Art of The Deal and takes Xi Jinping and Kim Jong Un to school. A wildly successful two-way summit convinces “Little Rocket Man” that he should join the Western Order, lest he end up on the wrong side of history.

Four-way US-North-South-China talks are held, where the Donald works his magic on his communist counterparts. After a series of 280-character demands, the peninsula is unified—on American terms. A flummoxed Xi is forced to cede China’s buffer state to the South Koreans. Kim, Moon and Trump share a giggle as the Chinese leader sheepishly signs the final declaration.

As the summit concludes, Kim steps onto the podium to make a closing statement. “A divided nation cannot be truly self-sufficient. A divided nation cannot control its destiny. Korea is one nation. The Korean people have made two approaches to secure their honor and prosperity. Neither is perfect, one has succeeded, and one has come short. It is in accordance with Juche, and the wishes of my father and of the Korean people, that I have signed this declaration proclaiming one Republic of Korea.” As a ceremonial gesture, Kim dons a MAGA hat and makes his departure.

Trump, of course, is prepared for this. He had already ordered USFK to move up to the Yalu River, within sight of the People’s Liberation Army. To placate Xi, he had agreed to ensure that US forces would not come within 50 kilometers of the Chinese border—a demilitarized zone. In the wake of a new standoff, this time with the Chinese, Trump holds a rally back home. “This week, we didn’t just ‘end’ the Korean War,” he booms, making air quotes with his hands.

“We won it, we won it big league.”

Kim Jong Un certainly views his domestic situation as rather bleak, and the current governance and economic models deficient. After all, his agreement to meet Moon Jae-in on South Korean soil is indicative of Kim’s strong intent to change the status quo. The South Koreans, meanwhile, have been eager to seize the opportunity to end the divisive situation and, more importantly, their only true existential threat. The South Koreans should be careful not to seem too eager. Making short-term compromises for the sake of an agreement usually waters down the end product, as we saw with the Iran nuclear deal.

This gets at the motivations of these two stakeholders. Both Koreas hope for lessened military tensions, peace, and eventual reunification. That last hope, however, is not part of the Chinese calculus. While China hopes for peace and denuclearization on the peninsula, it cannot accept a unified Korea, especially not one with close relations to its greatest competitor, the United States. Although this factor has been largely absent in current commentary of the situation, it is perhaps one of the most concrete realities underlying the affairs of the peninsula. For better or worse, China has the largest say the peninsula’s outcome—barring anything fantastical like Scenario 4. And though the talk of great power politics may be reminiscent of the Cold War, China and the US are—and will be for the foreseeable future—the main arbiters of economic, military, and political power in the world, especially in the Pacific. Korean relations with both powers have brought tremendous development in the South and great political power in the North. This is not to say the Koreas are mere puppets of the greater powers, but rather to drive home the reality that current and future developments will be greatly influenced by the wants of China and the US. Realistically, then, reunification is out of the picture.