Europe and Mankind—English translation

Translator’s notes

Europe and Mankind is an interesting essay written by Nikolai Sergeyevich Trubetzkoy (1890–1938), who happens to be a first cousin thrice removed. He was primarily a linguist, but occasionally wrote on historical and sociological topics.

I merely stumbled upon this essay and found it extremely relevant to today’s world. However, there doesn’t appear to be an English translation available. I figured, I might as well translate it, and at the same time better understand the ideas of Nikolay Sergeyevich and others like him.

This is an interpretive translation. My emphasis is on getting across Nikolai Sergeyevich’s ideas as clearly as possible in standard modern English without distorting them. If you are a scholar interested in closely analyzing the exact words and terms used, you should look at the Russian original.

The original text contained section headings like “Preface”, “Part 1”, etc. Section titles (e.g. “Part 1: Chauvinism and Cosmopolitanism”), as well as summaries, notes, and highlights are added by me. Since this is my personal website, I want to share my thoughts and interactions with the text.

Europe and Mankind

By Nikolai Sergeyevich Trubetzkoy, Sofia, 1920.

Translated into modern English by Alexandr (Sasha) Trubetskoy, 2023.

Preface

Summary

The events of the Great War and Russian Revolution have moved Trubetzkoy to share his thoughts on European culture and identity.

He feels that more and more people agree with him and is now more comfortable sharing.

He hopes to rally his community of like-minded people to help implement these ideas.

It is not without hesitation that I offer this work to the world. The thoughts expressed here had coalesced in my mind some 10 years ago. Since then, I’ve discussed these topics with many different people, wishing either to test myself or to convince the other person. Many of these conversations and discussions turned out to be rather beneficial to me, since they forced me to flesh out and deepen my ideas and arguments. But they did not change my core ideas. Of course I could not possibly limit myself to casual conversations. In order to verify whether the theses that I’m defending are actually correct, I had to open these ideas up to a broader discussion, i.e. publish them. This I have still not done. And I haven’t done this because, over many conversations (especially early on), I got the impression that most of the people I came across simply did not understand what I was trying to say. They didn’t get it, not because I wasn’t expressing myself clearly, but because the majority of educated Europeans find these ideas inherently unacceptable, as if they go against some unshakeable psychological foundation that is the basis of European thought. People saw me as a purveyor of paradoxes, trying too hard to be original with my arguments. Needless to say, under those circumstances, I found debating neither meaningful nor beneficial, since a debate can only be productive when both sides understand each other and speak the same language. And because, at the time, I encountered nothing but misunderstanding, I did not consider it timely to make my thoughts public. I waited for a more opportune moment.

My decision to go to print is largely due to the fact that I am encountering more and more people who understand me; moreover, I am beginning to find people who agree with my core ideas. It turns out that many people have, completely independently, arrived at the same conclusions as I have. There seemed to have been a shift in the thinking of many educated people. The Great War and, in particular, the ensuing “peace” (which I am still forced to put in quotes), have challenged people’s faith in “civilized society” and have opened the eyes of many. We Russians are, of course, in a special situation. We have witnessed the sudden collapse of what we had called Russian culture. Many of us were shocked by the incredible speed and lack of difficulty with which it all happened, and many have pondered the causes of this phenomenon.

Perhaps this pamphlet may help some of my compatriots to clear up their own thoughts on the matter. Some of my positions could have been amply illustrated with examples from Russian history. This might have made my writing more lively and engrossing, but such digressions would have made the bigger picture less clear. In offering the reader these relatively new ideas, my main concern is to present these ideas clearly and in a logical progression. Furthermore, my thoughts apply not only to Russians, but to all other peoples which have in one form or another taken up European culture without actually having Romance or Germanic heritage. When I release this booklet to the world in the Russian language, I do so only because charity begins at home, and above all I’d like for my thoughts to be received and understood by my fellow countrymen.

In offering my thoughts to the reader’s attention, I would like to remind him of a choice he must personally make for himself. One of the following must be true: either the ideas that I am defending are false, and stand to be disproven logically; or these ideas are true, and we must draw practical conclusions from them.

Accepting the truth of the theses in this pamphlet obligates one to do further work. Having accepted these theses, one must develop and concretize them in order to apply them to real life, and to use this point of view to revisit many of the questions that present themselves throughout life. Many people these days are “reevaluating their values” in one way or another. For readers who do accept the theses I am defending, the last theses will serve to indicate the direction in which their “reevaluation” should go. There is no doubt that the work that proceeds from accepting these ideas, be it theoretical or practical, must be a collective effort. An individual can choose to abandon some idea or join a well-known cause, but it is the collective that must develop an entire system based on these thoughts, and put that system into practice. I invite anyone who shares my convictions to participate in this collective work. Thanks to a few serendipitous encounters, I am convinced that these people do exist. All they have to do is to join forces in an earnest, concerted effort. And if my pamphlet can serve as the catalyst to unite these people, I would consider my goal accomplished.

On the other hand, there are moral obligations that befall those who reject my theses as false. If the theses that I defend are truly false, then they are toxic and must be opposed. But since (dare I say) they are grounded in logic, then their refutation must be no less logical. They must be logically refuted in order to prevent those who have tasted these ideas from being misled. The author himself would forever toss aside these unpleasant, disconcerting thoughts that have haunted him for over a decade without looking back, if only someone would prove to him that they are logically false.

Part I: Chauvinism and Cosmopolitanism

Introduction

Summary

On the issue of nationalism, Europeans seem to fall on a spectrum with “chauvinism” on one end and “cosmopolitanism” on the other.

In reality, the two are the same thing. Cosmopolitanism is just a chauvinism of Romano-Germanic values.

There is a fairly large variety of positions that Europeans hold regarding the question of nationalism, but they are all on a spectrum between two extremes: chauvinism on one side, and cosmopolitanism on the other. All nationalism is basically a combination of elements of chauvinism or cosmopolitanism, a way of reconciling these two opposed notions.1

There is no doubt that this is how Europeans see chauvinism and cosmopolitanism—as two fundamentally, intrinsically opposite points of view.

However, we cannot accept this premise. The moment we take a closer look at chauvinism and at cosmopolitanism, we notice that there is no inherent distinction between the two. We see that the two are no more than two levels, two differing manifestations of the same underlying phenomenon.

The Chauvinist takes a priori the position that the best nation in the world happen to be his nation. His nation’s culture is better and more complete than all other cultures. His nation has the exclusive right to lead and dominate other nations, who must submit— and become assimilated, accepting the dominant faith, language and culture. Everything that stands in the way of his great nation’s final triumph must be swept away with force. This is how the Chauvinist thinks and, accordingly, acts.

The Cosmopolite rejects any distinction between nationalities. If such distinctions do exist, they must be annihilated. Civilized human society must be united and have a single culture. Uncivilized nations must accept this culture and join it, entering the family of civilized nations, so that together they may walk the one path of world progress. Civilization is the ultimate good, in the name of which we must sacrifice our national particularities.

When formulated this way, chauvinism and cosmopolitanism really do seem strikingly different. In the former, supremacy is claimed by the culture of a single ethno-anthropological group, while in the latter—by the culture of a post-national humanity.

But let’s take a look at what European cosmopolites include in their definition of “civilization” and “civilized society”. By “civilization” they mean to say the culture that was produced by the Germanic and Romance peoples of Europe. And “civilized nations" refers, first and foremost, to those same Germanic and Romance nations, and only then to nations that have accepted European culture.

And so we see that the culture that Cosmopolites believe should reign supreme, abolishing all other cultures, is the culture of the same specific ethno-anthropological group whose dominance the Chauvinist dreams of. There is no fundamental difference here. In fact, the national, ethno-anthropological and linguistic unity of every European nation is only relative. Each of these nations is a combination of different, smaller ethnic groups that have their own dialectical, cultural and anthropological features, but are related to each other by ties of kinship and common history that have created a stock of common cultural assets.

Thus, the Chauvinist, bestowing upon his nation the crown of creation and deeming them the sole bearers of all possible perfection, is in fact the champion of a whole group of ethnic units. Moreover, the Chauvinist wants other nations to merge with his nation, losing their national likeness.

When looking at other nations that have already done this, forfeiting their national identity and taking on the language, faith and culture of his nation, the Chauvinist will treat them as his own people. He will praise the others’ contributions to his nation’s culture—but, of course, only if this other nation has truly taken on a disposition that is sympathetic towards him, having completely abandoned their previous national mentality. To the nation that assimilated with the dominant nation, the Chauvinists always take a somewhat suspicious attitude, especially if the assimilation happened not long ago. But no Chauvinist fundamentally rejects the newly assimilated—we know, in fact, that among the European Chauvinists there are many people whose surnames and anthropological characteristics clearly show that, by origin, they do not belong to the people whose domination they so vehemently preach.

Now let us consider the European Cosmopolite. We see that, in essence, he is the same as the Chauvinist. The “civilization”, the culture that he considers to be the highest, to which all other cultures should bow down, also represents a known stock of cultural assets common to a group of ancestrally and historically related nations. Just as the Chauvinist ignores the particular characteristics of the individual ethnic groups making up his own nation, the Cosmopolite does away with the peculiarities of individual Romano-Germanic1 nations and takes only those things that they share in common. The Cosmopolite also recognizes the cultural value of the activities of non-Romano-Germanic nations who fully embraced Romano-Germanic civilization, who discarded everything that contradicted the spirit of the dominant civilization, and exchanged their national likeness for one that is pan-Romano-Germanic. This is exactly like the Chauvinist, who recognizes as “his own” those aliens and foreigners who managed to fully assimilate with the dominant nation! Even the hostility experienced by Cosmopolites towards Chauvinists—and in general to those who distinguish the cultures of individual Romano-Germanic nations—even this hostility has a parallel in the Chauvinist worldview. Namely, the Chauvinists are always hostile to any attempts at separatism by the various parts of their own nation. They try to erase and obscure all regional particularities that could disrupt their nation’s unity.

Therefore, as it turns out, there is complete parallelism between the Chauvinist and the Cosmopolite. It is essentially the same treatment of the ethno-anthropological group to which the person happens to belong. The only difference is that the Chauvinist takes a narrower ethnic group than the Cosmopolite. And in doing so, the Chauvinist nonetheless takes a group that is not entirely homogeneous—while the Cosmopolite, in turn, still ends up choosing a particular group.

Thus the difference is only in scale, not in principle.

Cosmopolitanism is Romano-Germanic chauvinism

Summary

Cosmopolitanism is pan-Romano-Germanic chauvinism.

It is founded on unconscious prejudice and the egocentric mentality that all people have—everyone thinks their group is superior.

When evaluating European cosmopolitanism, we must remember that terms like “mankind”, “human civilization”, etc. are highly nebulous terms that act as cover for very specific ethnographic concepts. The culture of Europe is not the culture of mankind. It is a product of the history of a particular ethnic grouping. Germanic and Celtic tribes, having been subjected to various degrees of Roman cultural influence, and having strongly intermixed amongst themselves, created a well-known, common way of life from elements of their own national culture and Roman culture. As a result of shared ethnographic and geographical conditions, for a long time they lived a shared existence, with a common history and way of life. Their constant communication with each other made their shared elements so numerous that they always unconsciously harbored a sense of Romano-Germanic unity. With time, like so many other peoples, they developed a thirst for studying the sources of their culture. The discovery of monuments to Roman and Greek culture brought to the surface the concept of a transnational world civilization, a concept that is very natural to the Greco-Roman world. We know that this concept was based, once again, on ethnic and geographical factors. In Rome, the “entire world” meant, of course, simply orbis terrarum—that is, the peoples inhabiting or gravitating toward the Mediterranean basin who developed a set of shared cultural assets as a result of constant contact, and who were finally unified by the homogenizing influences of Greek and Roman colonization and Roman military dominance. In any case, the cosmopolitan ideas of antiquity became the foundation of the European education. Falling upon the fertile soil of unconscious Romano-Germanic unity, these ideas generated the theoretical foundations for so-called European “cosmopolitanism”, more accurately described as simply pan-Romano-Germanic chauvinism.

These are the real-life historical foundations of European cosmopolitan theories. The psychological foundation of cosmopolitanism is the same as that of chauvinism. It’s a sort of unconscious prejudice, a certain mentality that is best called egocentrism.1 A person with a markedly egocentric personality unconsciously considers himself the center of the universe, of all creation; the best, the most perfect of all beings. When looking at two other beings, the being that is closer and more like him is better, while the one that is more distant is worse. Therefore, if this person belongs to any natural groups, he would consider those groups to be superior. His family, his socio-economic group, his nation, his tribe, and his race are better than all the others. Likewise, the species to which he belongs—the human species—is superior to all other mammals; mammals themselves are superior to all other vertebrates, and vertebrates in turn are superior to plants; and the organic world is superior to the inorganic world. In one way or another, nobody is free from this kind of thinking. Even science has not yet fully freed itself from this, and any scientific conquest towards liberation from egocentric prejudices comes with great difficulty.

There are many people whose entire worldview is permeated with egocentrism. Very few manage to escape it completely. But in its extreme manifestation it’s easily noticeable; its ridiculousness is apparent, and so it often elicits criticism, protest and ridicule. If a person is convinced that they are smarter and better than everyone else, and that they have everything going for them, they are usually mocked by those around them. And if that person is also aggressive, then they receive a well-deserved slap in the face. If a family is naively convinced that its members are all brilliant, beautiful geniuses, then they are laughed at by their acquaintances, who make amusing jokes about them. Such acute manifestations of egocentrism are rare, and they are typically met with resistance. It’s a different story when the egocentrism spreads to a broader group of people. Usually, at that point, there is also resistance, but breaking this kind of egocentrism is more difficult. More often than not, two egocentrically-minded groups fight it out and the winner is able to maintain their convictions. This takes place, for example, during class warfare or social struggle. The bourgeoisie that overthrows the aristocracy is just as convinced of its supremacy over all other classes as was the aristocracy. The proletariat that fights against the bourgeoisie also considers itself the salt of the earth, the best out of all the social classes.2

But the egocentrism there is fairly obvious, and people with a clearer head, those with a “broader view”, are usually able to rise above such prejudices. When it comes to ethnic groups, these same prejudices are harder to get rid of. In this regard, people’s sensitivity in understanding the nature of egocentric prejudices is far from evenly distributed. Many Prussian pan-Germanists harshly criticize fellow Prussians who hold the Prussian nation above all other Germans; they consider such “drunkard’s patriotism” laughable and narrow-minded. Yet, at the same time, the pan-Germanists have no doubt whatsoever that the German tribe as a whole is humanity’s crowning achievement – they’re not able to reach the level of Romano-Germanic cosmopolitanism. The Prussian Cosmopolite, meanwhile, resents his pan-Germanist compatriot, branding him a narrow-minded chauvinist. Yet the Cosmopolite fails to notice that he is very much a chauvinist himself, only a Romano-Germanic one, rather than a pan-German one. So it’s just a matter of the scope of one’s sensitivity; one person’s egocentric chauvinist feelings are slightly stronger, the other’s are slightly weaker. Either way, the sensitivity of Europeans to such questions is quite relative. We don’t find very many people who rise beyond so-called cosmopolitanism, i.e. Romano-Germanic chauvinism. Do we know of any Europeans who would be willing to recognize the cultures of so-called “savages”2 as equal in worth to the Romano-Germanic culture? I don’t think they exist.3

Everyone should reject both chauvinism and cosmopolitanism

Summary

Both Romano-Germans (Westerners) and non-Romano-Germans (non-Westerners) should condemn chauvinism because it is egocentric. Romano-Germans should also condemn cosmopolitanism, since it is a form of their egocentrism.

Non-Romano-Germans, however, are not acting egocentrically if they subscribe to cosmopolitanism. Nonetheless, they should condemn it, since “the message of the sermon more important than the personal identity of the preacher.”

From the above it is quite clear how a conscientious Romano-German should treat chauvinism and cosmopolitanism. He must acknowledge that one and the other are both based on an egocentric mentality. He must acknowledge that such a way of thinking is not logically sound, and thus cannot serve as a basis for any theories. Moreover, it should not be difficult for him to understand that egocentrism is inherently anti-cultural and antisocial, and interferes with cohabitation in the broad sense of the word, i.e. the free interaction of all beings. It should be clear to everyone that any kind of egocentrism can be justified only through force, and, as written above, it only goes to the winner. That’s why Europeans do not go further than their Romano-Germanic chauvinism—any nation can be conquered by force, but the whole Romano-Germanic tribe in its entirety is so physically strong that it cannot be physically subdued by anyone.

But the moment all this reaches the conscience of our hypothetical sensitive and conscientious Romano-German, a conflict occurs in his soul. His whole spiritual culture, his entire worldview is based on the belief that the unconscious spiritual life, and all prejudices based upon it, must give way to the conclusions of reason and logic; that any theories can be constructed only on a logical, scientific basis. His entire sense of right and wrong is based on the rejection of any principles that hinder the free interaction of people. All of his ethics reject the resolution of differences by brute force. But suddenly it turns out that cosmopolitanism is founded on egocentrism! Cosmopolitanism, the pinnacle of Romano-Germanic civilization, is grounded in principles that fundamentally contradict all of this civilization’s primary mantras. The universal religion of cosmopolitanism, it turns out, is founded on anti-cultural egocentrism. The situation is tragic, but there is only one way out. The conscientious Romano-German must forever reject both chauvinism and so-called cosmopolitanism, and hence, the entire spectrum of views on the “national question” that lies in between.

But what position should non-Romano-Germans take in relation to European chauvinism, as representatives of those peoples who never participated in the creation of so-called “European civilization”?

Egocentrism deserves condemnation, not only from the standpoint of only European Romano-Germanic culture, but from the standpoint of all cultures, for it is a starting point that is antisocial and that destroys all cultural communication between people. Therefore, if among non-Romano-Germanic peoples there are chauvinists preaching that theirs is the chosen people, and that all others should submit to their culture, such chauvinists should be fought by their fellow countrymen. But what if individuals from a non-Romano-Germanic nation appear, who preach not for the dominance of their own nation, but for the dominance of some other, foreign nation, offering their own countrymen to assimilate into this “world nation”? After all, there would be no egocentrism in such preaching—on the contrary, this would be highly allocentric. As a result, it is impossible to condemn this kind of preaching in the same way that we condemn chauvinism.

But, on the other hand, isn’t the message of the sermon more important than the personal identity of the preacher? If the domination of Nation A over Nation B were being preached by a member of Nation A, that would be chauvinism, a manifestation of egocentric thought. Such preaching should be met with resistance by Nation A as well as by Nation B. But would the whole thing really change if the voice of the preacher from Nation A were joined by someone from Nation B? Of course not – chauvinism is chauvinism. The main actor in this hypothetical situation is, of course, the representative of Nation A. His mouth articulates his will to subjugate, which is the true meaning of chauvinistic theories. Indeed, the representative of Nation B may even have a louder voice, but is less significant in essence. Person B merely believed Person A’s argument, took faith in the strength of Nation A, let Nation A take him over—or maybe was just financially bought. Person A stands up for himself, while Person B stands for someone else: B’s lips move, but it is essentially A who is speaking. Therefore we are always right to consider such preaching to be the very same chauvinism in disguise.

The hypnotic power of cosmopolitanism

Summary

It seems obvious that a culture shouldn’t preach its own self-destruction and assimilation into another culture.

Nonetheless, cosmopolitanism is spreading outside Europe and, in some cases, reaching new heights. This is because non-Romano-Germans are misled about its true intent.

All this reasoning, in general, is rather pointless. These are not things that are worth proving logically at length. It is clear to everyone how they would treat their fellow tribe member if that member began to preach that their people should renounce their native faith, language and culture, and try to assimilate with a neighboring people, say, People X. Everyone would definitely see that person as a madman, or as someone duped by People X, having lost all national pride—or, finally, as an emissary of People X, sent to spread propaganda for some appropriate compensation. In any case, behind this gentleman’s back, everyone would, of course, suspect him of being a chauvinist from People X, consciously or unconsciously controlled by their words. Our attitude toward such preaching would not depend at all on whether it came from a compatriot or a foreigner: we would always see it as emanating from the people whose dominance was being preached. There is no doubt that our attitude toward such preaching would be strongly negative. No normal people in the world, especially a people organized into a state, could voluntarily allow the destruction of their national character in the name of assimilation, even with a “superior” nation. To chauvinistic harassment by foreigners, any self-respecting nation would answer as Leonidas of Sparta did: “Come and take them.” They would defend their national existence with weapons in hand, even in the face of inevitable defeat.

This all seems obvious, yet there are many facts out in the world that contradict all of this. European cosmopolitanism, which, as we have seen above, is nothing more than Romano-Germanic chauvinism, is spreading among non-Romano-Germanic nations quite rapidly and with very little difficulty. Among the Slavs, Arabs, Turks, Indians, Chinese and Japanese, there are already very many of these cosmopolites. Many of them adhere to the ideology even more strictly than their European counterparts, in terms of rejecting national characteristics, in their contempt for any non-Romano-Germanic cultures, and so on.

What explains this contradiction? Why has pan-Romano-Germanic chauvinism been so indisputably successful among the Slavs, when even the slightest hint of Germanophilic propaganda would ring a Slav’s alarm bells? Why are Russian intellectuals vehemently repulsed by the idea that they might be a tool in the hands of German junker nationalists, while at the same time being totally comfortable with subordinating themselves to Romano-Germanic chauvinists?

The answer lies, of course, in the hypnotic power of words.

As stated above, the Romano-Germans were always so naively confident that they were the only people who could brand themselves as “humanity”, brand their culture as “human civilization”, and finally, brand their chauvinism as “cosmopolitanism”. With this terminology they were able to obscure the ethno-specific meaning of these concepts. In doing so, these concepts were made palatable to members of other ethnic groups. When Romano-Germans give foreign nations the more universal products of their material culture (military and transport technology), they also smuggle in ideas that are presented as “universal”, diligently covering up the ethno-specific nature of these ideas.

So the spread of so-called3 European cosmopolitanism among non-Romano-Germanic nations is purely a misunderstanding. Those who succumbed to the propaganda of Romano-Germanic chauvinists were misled by words like “mankind”, “humanity”, “universal”, “civilization”, “world progress”, and so on. All these words were understood literally, whereas in reality they concealed very specific and rather narrow ethnographic concepts.

Questions for cosmopolitanists

Summary

Non-Romano-Germanic “intellectuals” who were fooled by the Romano-Germans must understand their mistake. They must understand that the culture that they were presented under the guise of human civilization is, in fact, the culture of only a certain ethnic group – the Germanic and Romance peoples. Naturally, this insight would significantly change their attitude toward the culture of their own nation, forcing them to reconsider whether they’re doing the right thing by trying to impose a foreign culture and eradicate the features of their nation’s indigenous identity in the name of some “universal” (in fact, Romano-Germanic, i.e. foreign) ideals. They can answer this question only after a mature and logical examination of the Romano-Germans' claims to the title of “civilized humanity”. The decision to adopt Romano-Germanic culture or not should only be made after answering a whole series of questions, namely:

- Is it possible to objectively prove that the Romano-Germanic culture is superior to all other cultures that exist or have ever existed on Earth?

- Is it possible for one nation to fully adopt a culture that was developed by another nation, while at the same time maintaining anthropological separation between the two nations?

- Is inclusion into European culture (since such inclusion is possible) a good or bad thing?

These issues must be raised and, in one way or another, resolved by anyone who is aware of the essence of European cosmopolitanism as Romano-Germanic chauvinism. And only with an affirmative answer to all of these questions can global Europeanization be recognized as necessary and desirable. If any answer is negative, this Europeanization must be rejected and new questions should be raised:

- Is global Europeanization inevitable?

- How do we deal with its negative consequences?

In the following discussion, we will try to answer all of the questions that we’ve just asked. But in order for the answers to be correct and, most importantly, fruitful, we must invite the reader to temporarily, completely abandon egocentric prejudices, the idols of “human civilization”, and in general the thought process that is typical to Romano-Germanic science. This abandonment is not an easy thing, for the prejudices in question are deeply rooted in the consciousness of every “educated” European person. But we must abandon these things in order to remain objective.

Part II: Romano-Germanic Culture Is Not Superior

Any “evolutionary ladder” of cultures is illogical

Summary

Cultures can be grouped next to each other based on similarity.

But any linear ranking with a “start” and “end” has to be arbitrary.

We already pointed out above that Romano-Germanic cultural supremacism is based on an egocentric mentality. As we know, in Europe, this concept of the utmost perfection of European civilization is given a scientific-seeming foundation, but this foundation’s validity is just an illusion. The problem is that the understanding of evolution as it exists in European ethnic studies, anthropology and cultural history is itself permeated by egocentrism. The “evolutionary ladder”, “levels of development”—these concepts are all deeply egocentric. At their core lies the assumption that the development of the human species has followed, and continues to follow, the path of so-called world progress. This path is imagined to be a known, straight line. Mankind has been travelling along this straight line, but individual peoples have stopped at various points, as if walking in place; meanwhile, other peoples have managed to move along a bit further, stomping around at the next point, an so on. As a result, when we take a look at the bigger picture of mankind’s current existence, we can see the whole evolutionary process4—at each step of the way that mankind has travelled, there remains today some stagnant nation, stuck and walking in place. Thus the current human condition, taken as a whole, represents a sort of rolled-out, chopped-up film of evolution, and the differences between the cultures of various peoples represent different phases of overall human evolution, or different stages along the path of world progress.

If we suppose that this view of the relationship between evolution and reality is correct, we must admit that we are incapable of reconstructing the whole evolutionary picture. Indeed, in order to figure out which culture represents which evolutionary phase, we need to know exactly where lies the beginning, and where lies the end of this straight line of world progress. Only then can we determine what distance separates a given culture from the endpoints the aforementioned ladder of progress and, from there, determine that culture’s evolutionary rank. But we cannot determine the endpoints of evolution without first reconstructing the whole evolutionary picture. This results in a catch-22:5 we can’t create the whole evolutionary picture without knowing its endpoints, but to determine its endpoints, we need to create the whole picture. Clearly, the only way to escape this catch-22 is to unscientifically, irrationally claim that one particular culture or another is an evolutionary endpoint. We cannot arrive at such a claim scientifically or objectively since, in this framework, a single culture by itself cannot contain any information on where it is along the evolutionary line. Objectively, the only thing we see is traits of greater or lesser similarity between various cultures. We can group the world’s cultures based on these traits, so that more similar cultures are closer together, while more distinct cultures are put farther apart. We cannot do anything beyond this while remaining objective. Even if we managed to create a continuous chain of cultures based on similarity, we would still not be in a position to objectively determine where the ends of this chain would be.

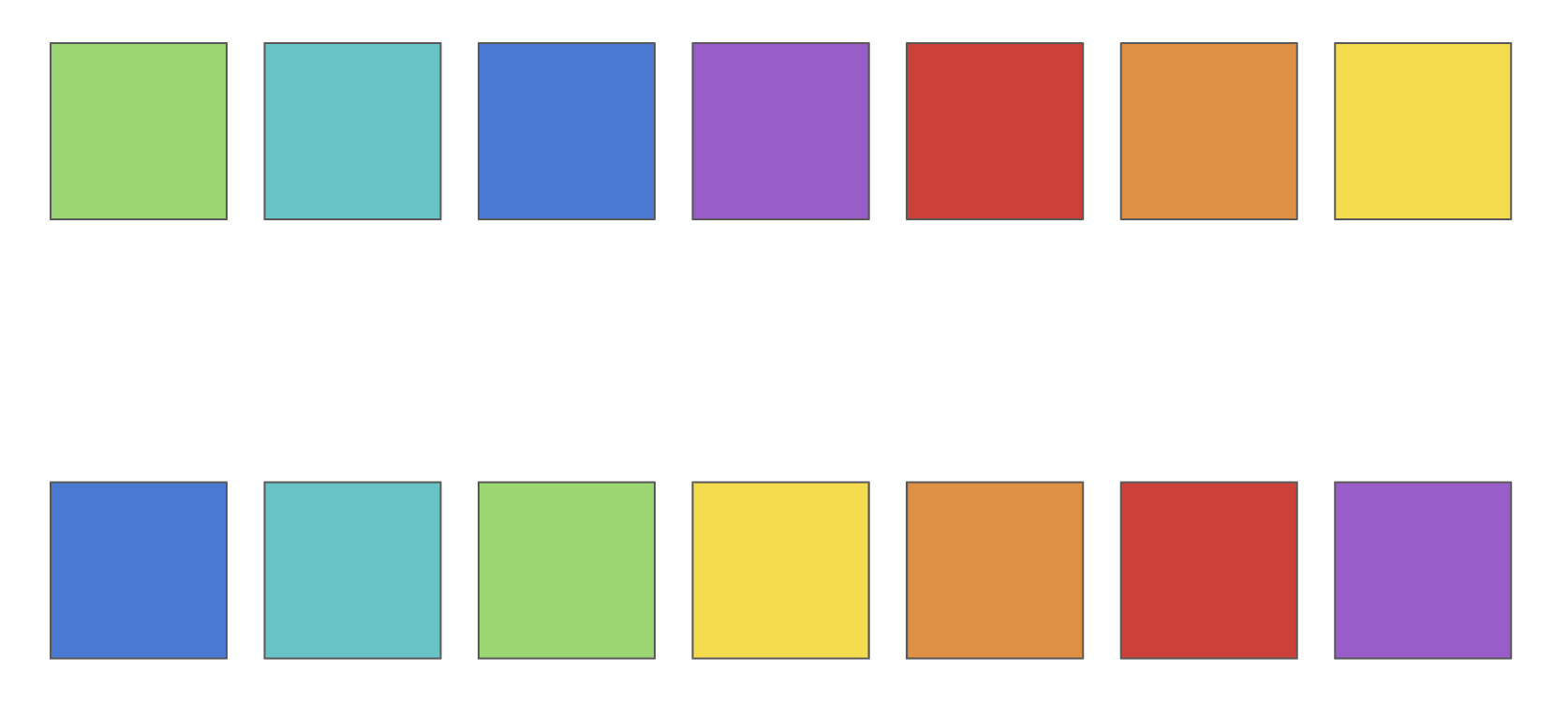

Let’s clear up this idea with an example. Imagine seven squares, each of which is colored with one color of the rainbow. We line these squares up by color and list them, left to right: green, cyan, blue, violet, red, orange, yellow. Now jumble these squares and ask a volunteer who hasn’t seen the original sequence to line them up, so that every color is between two similar colors. Since our volunteer doesn’t know how the squares were initially set up, it’s clear that if they were to arrange them in the exact same order as above, they would have done so purely by chance. Moreover, the probability of them doing so is 1 in 14.

A scientist who attempts to arrange the present-day human nations and cultures according to an evolutionary sequence finds himself in the exact same position as our rainbow-arranging volunteer. Even if he places each culture between the two cultures that are most similar, he will still never know where to start—just as in our rainbow example, the volunteer doesn’t know to start with the green square, and to place the cyan square to the right of it, rather than to the left. The only difference is that there are far more than seven cultures, and thus there will be far more than 14 possible arrangements. So the probability of finding the “correct” sequence is far smaller.

So if the understanding of evolution that currently prevails in European science is correct, then it is impossible to reconstruct the picture of human cultural evolution. And yet, Europeans assert that they have determined what the general course of this evolution looks like. What is the explanation here? Has there truly been a miracle, have European scientists really received from some mysterious source a supernatural revelation, allowing them to identify the endpoints of an evolutionary sequence?

The “scientific” view of human evolution is egocentric

Summary

European scientists seeking to describe a “ladder of human evolution” end up placing Romano-Germanic culture at the top for egocentric reasons.

Such a ladder is, in fact, just a ranking of similarity to Romano-Germans.

If we look closely at the result of European scholars' work in creating their framework of human evolution, it immediately becomes clear that the source of this supernatural revelation was simply their own egocentric mentality. It was this mindset that showed Romano-Germanic scientists, ethnologists and cultural historians where to look for the beginning and end of human development. Instead of remaining objective and, upon seeing the logical dead end, attempting to find the source of this dead end and the incorrectness of the overall understanding of evolution, instead of attempting to fruitfully rectify this understanding, Europeans simply took the pinnacle of human evolution to be themselves and their culture. Naively convinced that they have found one end of the evolutionary sequence, they quickly built out the rest of the sequence. It never occurred to any of them that acceptance of Romano-Germanic culture as the pinnacle of evolution is purely arbitrary, and is a grotesque case of petitio principii. Their egocentric mindset turned out to be so rigid that nobody doubted the correctness of this position, and it was accepted by everyone without discussion, as if it were self-evident.

As a result, we get the “ladder of human evolution”. The Romano-Germanic peoples, and those that have wholly embraced their culture, stand at the top. One step below are the “cultured ancient peoples”, i.e. those peoples whose culture is most closely related to that of the Europeans. Then there are the cultured peoples of Asia: their literacy, good governance and some other cultural features allow one to find some similarities to the Romano-Germanics. The “ancient American cultures” (Mexico, Peru) are viewed in a similar way; these cultures resemble the Romano-Germanics even less, and are therefore placed somewhat lower on the ladder. Nonetheless, all of the abovementioned peoples have enough cultural traits in common with the Romano-Germanics that they are bestowed the flattering title of “cultured”. Below them are the “savages”. These are the representatives of mankind that have the least similarity to modern Romano-Germanics.

According to this evolutionary ladder, the Romano-Germanics and their culture really do represent the height of human achievement. Of course—the Romano-Germanic cultural historians humbly add—with enough time, mankind will travel even farther, and it’s possible that the inhabitants of Mars are already culturally superior to us, but here on Earth, we Europeans are superior and above everyone else. But this evolutionary ladder cannot possess any objective evidentiary value. It isn’t that Romano-Germanics see themselves as the “pinnacle of creation” because objective science has set up the aforementioned ladder; on the contrary, European scientists place the Romano-Germanics at the top of this ladder because they were convinced a priori of their superiority. The egocentric mentality played a decisive role here. Objectively speaking, this entire ladder consists of a classification of peoples and cultures according to their lesser or greater similarity to modern Romano-Germanics. It is the judgmental aspect, transforming this classification into a ladder with rungs of perfection, that lacks objectivity, and is introduced via a subjective egocentric mentality. Therefore the classification of peoples and cultures that is accepted in European science cannot objectively prove the supremacy of Romano-Germanic civilization over the cultures of other peoples. Even if something is self-evidently good, it does not follow that it’s the best in the world.

Trivial arguments for Romano-Germanic superiority

Let us look at the evidence that is brought up in favor of the overall supremacy of the Romano-Germanic civilization that stands atop the “evolutionary ladder”, as opposed to the “savage” cultures that sit at the “lowest level of development”. Amazingly, all this evidence is based on either the petitio principii of egocentric prejudice, or on the optical illusions that result from this mentality. There is no objective, scientific evidence whatsoever.

Military superiority

Summary

The most basic and widespread evidence consists of the fact that Europeans, it is said, are winning against the savages; that every time savages go into battle against Europeans, the battle ends in “white” victory and the “savages’” destruction. The vulgarity and naivety of such an argument must be evident to any objectively-minded person. It clearly demonstrates the extent to which the veneration of brute force, which featured nontrivially in the national character of those tribes that would create European civilization, is alive and well to this day in the consciousness of every descendant of the ancient Gauls and Germanics. The Gaulish “Vae victis!” and Germanic vandalism, systematized and deepened by Roman military traditions, are displayed here in all their glory, albeit masked in a semblance of objective science. Meanwhile, this argument comes up even among the most enlightened European “humanists”. Deconstructing the failure of its logic is, of course, not worth trying. Nonetheless, Europeans do attempt to mold it into a scientific force, giving it a foundation in the form of a theory of “fighting for survival” or “adapting to the environment”, but in the end they cannot sustain this historical viewpoint. They are constantly forced to admit that victory often falls in the hands of peoples “less cultured” than their vanquished adversaries. History is full of examples of nomads defeating sedentary peoples, even though nomadic peoples differ in their way of life from modern Romano-Germans sufficiently to place them below any settled nation. All of the “great cultures of Antiquity”, as they are called in European learning, were destroyed precisely by “barbarians”. And even though the excuse is frequently given that these cultures, at the time of their destruction, had already fallen into a so-called state of decay, there is a wide range of examples where this cannot be conclusively demonstrated. Thus, since European learning cannot claim the position that the victorious peoples are always culturally superior to the vanquished peoples, they cannot make any positive conclusions from the fact that Europeans have militarily defeated the savages.

Self-evidence

Summary

There is an argument that European culture is self-evidently superior, since “savages” cannot grasp it.

But this does not mean they are inferior, since the same could be said of European grasping “savage” cultures.

There is another argument that is no less popular, but even less coherent. It consists of the idea that “savages” are incapable of perceiving certain European concepts, and are therefore considered to be an “inferior race”. The egocentric mentality here is especially strong. Europeans completely forget that if “savages” are incapable of perceiving some of the ideas of European civilization, then Europeans are likewise equally incapable of comprehending ideas from the savages’ culture.

There is an oft-repeated story about a Papuan who was taken to England, educated in school and even taken to university. Soon, however, he felt a longing for his homeland, fled to Papua, and threw off his European clothes to live like the “savage” he was before he was taken to England—not a trace was left of any European cultural concepts. And yet, people seem to completely forget the numerous stories of Europeans who decided to “simplify their lives,” settling among “savages”, but who returned to Europe and to all the trappings of a European lifestyle after realizing they were unable to keep up the charade. They point out that embracing European civilization is so difficult for the “savages” that many of them, after attempting to “become civilized”, went insane and became alcoholics.

However, in those rather rare cases when a European did earnestly attempt to assimilate into the culture of some wild tribe—embracing not just the superficial, physical lifestyle of the tribe, but its religion and beliefs as well—the majority of these “weirdos” met the same fate. It is sufficient to mention the talented French painter Paul Gauguin, who tried to become a real Tahitian, and paid for his attempt first with insanity, and then alcoholism, dying ingloriously after a drunken brawl. Clearly it is not the case that “savages” are less developed than Europeans, but rather, that the development of Europeans and savages goes in different directions, and that Europeans and “savages” differ to the fullest extent in their lifestyles and in the ways of thinking that they generate. Full assimilation into such a foreign mode of being is impossible for both sides, precisely because the mindset and culture of “savages” has almost nothing in common with the mindset and culture of Europeans. But since this lack of possibility remains commutative, making it just as difficult for a European to become a savage as it is for a “savage” to become a European, one cannot draw any conclusions about who is “higher” and who is “lower” in “development”.

Psychological arguments for superiority

"Savages" are not childish

Summary

“Savages” may appear psychologically childish to Europeans, but this perception goes both ways.

When we fail to recognize or understand acquired traits from a distant culture, we see only the innate ones, giving the impression of a childlike level of development (since children have fewer acquired traits).

We’ve taken apart some arguments in favor of the superiority of Europeans over “savages”. Although they may sometimes appear in scientific literature, the “arguments” presented so far have consisted of layman’s reasoning, naive and superficial. The scientific literature is dominated by other arguments, which appear far more serious and solid. However, upon more careful examination, these quasi-scientific arguments turn out also to be based on egocentric prejudices. In science, we find that the mentality of savages is often likened to the mentality of children. The comparison is practically self evident, for if observed directly, savages really do seem to Europeans like adult children. From there they conclude that the savages have “stopped developing” and therefore are lower than the proper adult Europeans. Here the European scientists once again demonstrate a lack of objectivity. They completely ignore the fact that the “adult child” impression when Europeans meet “savages” is mutual, i.e. the savages also regard the Europeans as adult children. From a psychological standpoint, this is a very interesting fact, and we must look for its explanation within the very essence of what Europeans mean by the word “savage”. We stated earlier that the word “savage” is used by European scientists to designate those peoples whose culture and mentality differ the most from modern Romano-Germans. This is where we may find the answer to the aforementioned psychological quandary. We have to bear in mind the following propositions:

-

Every person’s psyche consists of innate and acquired elements.

-

Among innate psychological traits, we must distinguish between traits belonging to the individual, to his family, his tribe, his race; as well as traits common to humans, mammals, and then animals in general.

-

Acquired traits depend on the environment in which the given individual lives, and on the traditions of the individual’s family and social group, and on the culture of his nation.

-

In very early childhood, the entire psyche consists exclusively of innate traits; as time passes, those traits are increasingly joined by traits that are acquired. Moreover, as a consequence of trait acquisition, some innate traits may be softened or may disappear entirely.

-

When considering any person’s mentality, we only have direct access and understanding of those traits that we have in common with that person.

From these propositions it follows that when two people meet each other, if they belong to exactly identical environments and upbringings within the exact same cultural traditions, they both understand virtually all of each other’s psychological traits. This is because they have almost all of their traits in common, except for a few innate ones. But when two people meet each other and come from two completely different cultures that look nothing alike, then each person will only see and understand a few of the other’s innate traits, without understanding (or perhaps even noticing) the acquired ones, since in this domain the two individuals have nothing in common. As the observer’s culture becomes more and more different from that of the observed, the observer will be able to understand fewer and fewer of the other’s acquired psychological traits; the mentality of the other will appear to the observer to consist entirely of traits that are innate. However, a psyche that is dominated by innate traits over acquired ones always gives the impression of being rudimentary. We can imagine any psyche as a fraction where the numerator is the sum total of acquired traits, while the denominator is the sum total of innate traits that are accessible to us. The smaller this fraction (i.e. the greater the ratio of the denominator to the numerator), the more rudimentary this psyche will appear. From the above propositions, the third and fifth indicate that this fraction will be smaller if the culture and society of the observer is more different from those of the observed.

Since “savages” are, in other words, those peoples whose culture and way of life differ the most from modern Europeans, it is clear that their psyche would appear to Europeans as exceptionally rudimentary. But from everything we have stated above, it is also clear that such an impression would have to be mutual. The conception of “savages” as “adult children” is based on an optical illusion. In savages, we only perceive the innate traits, since they are the only ones we have in common (proposition 5). The acquired traits are entirely alien and incomprehensible to us, since they are based on the savage’s cultural traditions (proposition 3), which are entirely different from ours. But a mentality where innate traits predominate while acquired traits are nearly absent is the mentality of a child (proposition 4). This is why we conceive of the “savage” as childlike.

There is another circumstance that plays into this conception. If we were to compare the mentalities of two children, a little “savage” and a little European, we would find that from a psychological standpoint the children are closer to one another than their fathers are. They do not yet have the acquired traits that are to appear later, but they have many common elements as part of the universal human, mammal and animal psyches; the differences attributable to racial, tribal, family and individual psyches are not so great. Over time, some of this shared supply of innate traits will be displaced or modified by acquired traits, while other innate traits will remain unaffected. But what traits are acquired will differ between the two subjects. The savage will lose trait A, but traits B and C will be preserved; the European will lose trait B, while traits A and C are preserved. Furthermore, the savage will acquire a beneficial trait D, while the European will acquire a beneficial trait E. When the adult European meets the adult savage and observes him, he will find in the savage’s psyche traits B, C and D. Of these traits, D will turn out to be completely strange and incomprehensible for the European, because this part of the savage’s psyche, an acquired trait, stands in connection with the savage’s culture, which has nothing in common with that of Europe. Trait C is held in common by the adult savage and the adult European, and therefore it is quite understandable to the latter person. As for trait B, it is not in the psyche of the adult European, but this European remembers that he had this trait in early childhood, and can observe it now in the psyche of the children of his nation. Thus, the psyche of the savage should inevitably appear to the European as a mixture of elementary features of adult psychology and of childlike traits. Needless to say, the European’s psyche would appear in the same way to the savage, for the same reasons.

"Savages" are not like animals

Summary

The optical illusion that we just talked about is also the cause of another phenomenon, namely, the similarities that Europeans find between the psychology of savages and the psychologies of animals. We stated above that, psychologically, there is little difference between a savage child and a European child. If we take these two kids and add a young animal, then we would have no choice but to acknowledge that these three creatures have some things in common—mammal-wide traits or animal-wide traits. There may not be very many of these traits, but nonetheless they exist. Let us suppose they are called X, Y and Z. Later in life, the little European develops and loses trait X. Meanwhile, the savage loses Y, while the animal preserves all X, Y and Z. But those animal traits that are preserved by these creatures are, of course, preserved in a slighly different form compared to how they were displayed in childhood, for an adult animal’s psychological traits always differ in known ways from the psychological traits of the young animals from which they developed. Therefore, traits X, Y and Z take on the adult forms X', Y' and Z', which means the European adult shows Y' and Z' while the adult savage shows X' and Z'. When the adult European observes the adult savage, he sees in him, among other things, trait X'. How does he perceive this trait? It is absent in his own psyche. In the European’s tribe, the children have it in a different form, namely X. But in the psyche of mature animals the European can directly see X'. Naturally, he determines that this is an “animal” trait, and by virtue of the savage having this trait, he will consider the savage to be the closest human to an animal level of development. All of this, of course, applies to the savage, who sees trait Y' in the European and makes an analogous conclusion based on the absence of this trait in him, and the presence of it in animals.

Extension to all cultures

Summary

Thus, the idea of the simplicity of the savage’s psyche, of its similarity to the psyche of a child or an animal, is based on an optical illusion. Even outside the context of savages—i.e. nations that are maximally culturally different from modern Romano-Germans—this illusion remains powerful, applying to all nations with non-Romano-Germanic culture. The difference is only in the degree of illusion. When observing a member of a “foreign” culture, we will understand only those acquired psychological traits that we have in common, which is to say, those that are connected to cultural elements we hold in common. Traits that are acquired but based on elements of his culture without a parallel in ours will remain incomprehensible to us. As for innate psychological traits, almost all of them will appear understandable to us, and some of them will appear childish. We will understand the innate psychological traits of this observed nation almost entirely, but will only grasp those acquired traits that are similar to our culture, so we will always incorrectly judge the ratio of innate to acquired traits, with a bias toward seeing more innate traits. Moreover, this bias will be stronger when a foreign culture differs more strongly from ours. Naturally, therefore, the mentality of a nation with a culture that differs from ours will always seem more elementary than our own mentality.6

Notice, by the way, that such an evaluation of another’s mentality can be seen not only between two nations, but also between different social groups of one nation, if the social differences within this nation are very strong and if the upper classes have adopted a foreign culture. Many Russian intellectuals, doctors, officers and nurses, when speaking to the “common folk”, say that they are “adult children”. On the other hand, the “common folk”, based on their fairy tales, see in the “baroness” a well-known eccentricity and naive, juvenile psychological traits.

The “historical argument”

Summary

Despite the fact that the European conception of the “savage” psyche is based on an illusion, this conception still play a prominent role in all the quasi-scientific contructions of European ethnology, anthropology and history of culture. Of all the ways this has affected the methodology of the aforementioned fields, the most significant has been that it allowed Romano-Germanic scholars to put a diverse set of the Earth’s peoples into a group called “savage”, “uncultured” or “primitive”.7 We already mentioned that these terms encompass nations whose culture is maximally different from that of Romano-Germans. This is the only characteristic these nations have in common. This characteristic is purely subjective, and is defined negatively. But as soon as it created the optical illusion that gave rise to the Europeans' one-dimensional characterization of all these nations' mentalities, the Europeans took it as an objective and positive indicator. They united all the nations whose culture differed most from Romano-Germans under the label “primitive”. European scholars refuse to reckon with the fact that this groups together nations that are nothing alike (for example, Eskimos and Kaffirs8), since distinctions between various “primitive peoples” are based on characteristics of cultures equally far from Romano-Germanic culture, all equally alien and incomprehensible to a European. Thus they are neglected by scientists, who consider the characteristics secondary or insignificant. And this group—this concept of “primitive peoples” that is founded, in essence, on subjective and negative perceptions—is treated uncritically by European science as a real and homogeneous quantity. Such is the power of the egocentric mindset in European evolutionary science.

This illusion, and the associated habit of qualifying nations based on their degree of similarity to Romano-Germanic culture, is the basis for another argument in favor of the superiority of Romano-Germanic civilization over all other cultures of the world. This argument, which can be called the “historical” argument, is considered in Europe to be the strongest—and it is one that cultural historians are especially eager to cite. In essence, it says that the ancestors of modern Europeans were originally also savages, and therefore, modern savages can be tought of as still existing at a stage of development that Europeans have long since passed. This argument is supported by archeological findings and ancient historians' descriptions demonstrating that the lifestyle of modern Romano-Germans' ancestors was marked by the same features as that of present-day savages.

The illusory nature of this argument becomes apparent as soon as we remember that the concept of “savage” or “primitive” nations is itself artificial, since it unifies extremely diverse tribes from across the globe based on just one characteristic, their utmost dissimilarity to modern Romano-Germans.

Just like any culture, European culture has been constantly changing as has arrived at its present form only gradually, as the result of a long evolution. In each historical era, this culture was different in some way. Of course, in eras closer to modernity, the culture of Europeans' ancestors was closer to its present form, compared to more distant eras. In the most distant of eras, the culture of the nations of Europe differed the most from the modern civilization—it was then that the culture of Europeans' ancestors was maximally different from the modern culture. But all cultures that are maximally different from modern European civilization are invariably placed by European scholars into the general category of “primitive cultures”. So, of course the culture of the distant ancestors of modern Romano-Germans must fall into that same category. No positive conclusions can be made from this. Since the term “primitive culture” is defined negatively, the mere fact that the epithet “primitive” is applied by European scholars to the most ancient of Romano-Germanic ancestors as well as to modern Eskimos and Kaffirs says nothing about how these cultures are similar to each other, only that they are dissimilar to modern European civilization.

Why "savages" always regress or stagnate

Summary

In this case, the distance \(AC=AB\) . In other words, it would turn out that this “savage” culture in a previous historical era different maximally from modern European culture. And since all cultures maximally different from European civilization are tossed by European science into big “primitive” pile, the European scholar in this case would not see any progress. He would instead recognize immobility, stagnation, no matter how great the path from C to B representing the trajectory taken by the “savage” culture during this historical epoch.

The second case: C lies within the circle. In this case the distance \(AC<AB\) . In other words, the savage’s culture went farther and farther from the point representing modern European culture. It is clear that the European scholar, considering his civilization the pinnacle of earthly perfection, could call this movement only a “regression”, “fall” or “ensavagement”.

Finally, the third case: C is outside the circle. Here the distance \(AC>AB\) , i.e. greater than the maximum distance from the culture of modern Romano-Germans. But values above the maximum are not perceptible to the human mind and are not accessible to the senses. The worldview of the European, standing at point A of our diagram, is limited by the circumference of our circle, and everything beyond the limits of the circle is no longer distinguishable. Therefore the European must project point C onto the circle to create C', which leads to the first case—the appearance of stagnation.

Just as how he treats the savages, the European evaluates the histories of other nations whose culture is closer or farther from modern Romano-Germanic culture. Strictly speaking, real “progress” is seen only in the history of Romano-Germans themselves, since it naturally features a constant, gradual approach towards the modern condition of Romano-Germanic culture, which is arbitrarily declared the peak of perfection. As for the histories of non-Romano-Germanic nations, if a history does not end in the adoption of European culture, then all its recent stages—those closest to the present day—would have to be viewed by European scholars as stagnation or decline. If a non-Romano-Germanic nation gives up its national culture and begins blindly copying Europeans, only then do Romano-Germanic scholars delightfully remark that this nation has “joined the path of human progress”.

And thus the “historical argument”, the strongest and more convincing in the eyes of Europeans, turns out to prove just as little as all the other arguments in favor of the superiority of Romano-Germans over savages.

The knowledge argument

Summary

They tell us, “Compare the contents of the mind of a cultured European with that of some Bushman, Botocudo or Vedda—is the superiority of the former over the latter not apparent?” But we maintain that the superiority here is only subjective. As soon as we allow ourselves to investigate the matter in good faith without prejudice, the self-evidence disappears. A savage, a good savage hunter-gatherer who has all the qualities that are valued in his tribe (since only such a savage can be compared to a real cultured European), possesses in his mind a huge reserve of all sorts of knowledge and information. He has perfectly studied the life of the environment that surrounds him, and knows all the animals' habits, such subtleties of their lives as would escape the keen eye of the most attentive European naturalist. All this knowledge is kept in the savage’s mind in a manner that is not at all disorganized. It is systematized—albeit not by the same set of criteria that a European scientist would use, but by another set, more convenient for the practical purposes of hunting. Aside from this practical and scientific knowledge, the savage’s mind contains an often very complex mythology of his tribe, its moral code, its rules of etiquette (which can be quite complex), and finally, a more or less significant repository of his nation’s oral literature. A savage’s head is bursting with material, despite the fact that its contents differ from that of a European’s head. And because of this difference in the substance of the intellectual life of a savage and a European, their mental contents should be considered incomparable and incommensurable, which is why the question of the superiority of one over the other should be considered unanswerable.

They point out that European culture is in many ways more complex than a given savage culture. However, this kind relationship between the two cultures is not observed when considering every aspect. Cultured Europeans are proud of the refinement of their manners, the finesse of their courtesy. But there is no doubt that the rules of etiquette and conventions of communal living in many savage cultures are much more complex and elaborate than those of Europeans, not to mention that all members of the “savage” tribe obey this code of etiquette without exception, while the Europeans' etiquette is the domain of only the uppermost classes. In taking care of their appearance, “savages” often show much more complexity than many Europeans: remember the sophisticated tattoo techniques of Australians and Polynesians or the most complicated hairstyles of African beauties. Even if we attribute all these complications to some amount of impractical oddity, there are in the life of many savages some undoubtedly practical institutions that are much more complex than the corresponding European ones. Take, for example, attitudes towards sexual life, family and marriage law. How rudimentary is the solution to this issue in the Romano-Germanic civilization, where the monogamous family exists officially, protected by law, while unbridled sexual freedom flourishes alongside it, which society and the state in theory condemn but in practice allow. Compare this with the elaborate institution of group marriage in Australia, where sexual activity is strictly regulated and, in the absence of individual marriage, measures are nevertheless in place both to provide for children and to prevent incest.

In general, it is hard to say much about the degree to which a culture has reached perfection. Evolution tends just as often towards simplicity as it does towards complexity. Levels of complexity, therefore, can in no way serve as a measure of progress. Europeans are well aware of this, and only apply this measure when it is convenient for their own purposes of self-glorification. In cases when another culture—for instance, a given savage culture—is in some form more complex than the European one, Europeans not only reject complexity as a measure of progress, but even on the contrary declare that, in this case, complexity is a sign of “primitiveness”. This is how European science interprets all the aforementioned examples: the complex etiquette of savages, their care for complex body decorations, even the intricate Australian system of group marriage—all this turns out to be a manifestation of a low degree of culture. Notice that Europeans here cannot refer to their beloved “historical argument”, dismantled above: in the prehistory of the Gauls and the Germans (and even the Romans themselves) there was never a moment when all the aforementioned, ostensibly primitive, sides of “savage” life would have been manifested. Some ancestors of Romano-Germans had no conception of careful body decorations, tattoos or fantastically complicated hairstyles, they neglected politeness and “manners” much more than modern Germans and Americans, and the family was structured in the same way from time immemorial. There are a number of other cases where Europeans do not consider the historical argument, where its logical application would not favour of European civilization. Much of what in modern Europe is considered to be the cutting edge of civilization or the peak of yet-to-be-achieved progress is found in savages, but is then declared a sign of extreme primitiveness. Futuristic images painted by Europeans are considered a sign of high refinement of aesthetic taste, but totally similar works by “savages” are just naive attempts, the first awakenings of primitive art. Socialism, communism, anarchism—these are all “shining ideals of the highest progress to come” only when they are preached by a modern European. When these “ideals” are realized in the life of savages, they are immediately designated as a manifestation of primitive savagery.

There is no objective proof of the superiority of Europeans over savages, and there never will be, because when comparing different cultures, Europeans know only one measure: what is like us is better, and more perfect, than anything that is not like us.

But if this is the case, if Europeans are not more perfect than savages, then the evolutionary ladder, which we talked about at the beginning of this chapter, should collapse. If the ladder’s top rung is not higher than the bottom rung, then clearly it is also not any of the other rungs. Where we used to have a ladder, we now have a horizontal plane. Instead of the principle of ordering nations and cultures by levels of perfection, we have a new principle of equality and qualitative incommensurability of all cultures and nations of the globe. The idea of appraising cultures should be forever banished from ethnology and cultural history, as well as from all evolutionary sciences in general, because appraisal is always based on egocentrism. There is no “higher” or “lower”. There is only “similar” and “dissimilar”. Declaring those who are similar to us to be higher and those who are different to be lower is arbitrary, unscientific, naive, and finally, just plain stupid. Only by completely overcoming this deep-rooted egocentric prejudice and driving its consequences out of the very methods and conclusions that have so far been built on it, will European evolutionary sciences—in particular ethnology, anthropology and cultural history—become real scientific disciplines. Until then, they are at best a means of tricking people and justifying, in the eyes of Romano-Germans and their henchmen, imperialist colonial policies and vandalistic exploitation9 by the “great powers” of Europe and America.

And so, to the first of the above questions—“Is it possible to objectively prove that the Romano-Germanic culture is superior to all other cultures that exist or have ever existed on Earth?"—we must answer, no.

Part III: Full Assimilation Is Impossible

Now we will try to answer the question, “Is it possible for one nation to fully assimilate into a culture created by another nation?” By “fully assimilate” we mean, of course, to adopt the culture of a foreign nation in such a way that the assimilated nation sees this culture as theirs, and the culture continues to develop within the assimilated nation in total lockstep with its development within the nation from which it was borrowed, such that both the creators of the culture and the borrowers merge into a single cultural whole.

Gabriel Tarde’s theory of cultural invention

Summary

To answer a question asked in this form, we must, of course, know the laws of the life and development of cultures. By the way, European science knows almost nothing in this area, since it is located on the same false path as the all the European evolutionary sciences, thanks to the abovementioned egocentric prejudices. The field of sociology still has not been able to develop objective scientific methods, much less any credible conclusions, and remains on par with alchemy. Some correct opinions on the method sociology should use and some truthful views on the real nature of the mechanics–or dynamics–of social phenomena can be found scattered among individual European sociologists, who, nonetheless, fail to hold true to their own methodological principles and invariably fall into an egocentrism-based generalization about the development of “mankind”. This passion for hasty generalizations, which are always wrong since they are based on false notions of “humanity”, “progress”, “primitiveness”, etc., is a passion that exists in all sociologists and makes it especially difficult to make use of their findings.

The Frenchman Gabriel Tarde, who unfortunately was relatively little known and wrongly evaluated in Europe, was the greatest European sociologist of the last century. He was perhaps closer to the truth than others in his general views on the nature of social processes and on the methods of sociology. But even this erudite scholar was ruined by a passion for generalization and a desire to immediately paint a picture of the entire evolution of “mankind” after defining some elements of social life. Moreover, imbued as all Europeans are with egocentric prejudices, he is unable to stand at a vantage point where cultures are equivalent and qualitatively incomparable. He is unable to conceive of “mankind” as anything other than a coherent whole, whose different parts located at different steps of an evolutionary ladder. And finally, he is unable to break with the idea of “universal” or “world progress”. Thus, although we stick to Tarde’s sociological teachings at a number of important points, we nevertheless have to make some very significant amendments to his theory. But this is the sociological system we will use to try to answer the question posed above.

The life and developent of any culture consists of the continuous emergence of new cultural assets. By “cultural assets” we mean any worthwhile human creations that become the common heritage of the creator’s compariots. These can be legal norms, works of art, institutions, technical devices, scientific principles or philosophical propositions – since all of these things meet certain physical or spiritual needs, or have been adopted by all or some of the people to satisfy such needs. In general, we will call the emergence of a new cultural asset an “invention”. Each invention is a combination of two or more already existing cultural assets or their various elements, although an invention cannot be cleanly divided into its components, and is always greater than the sum of its parts, having the added value of the combination itself, as well as an imprint of the personality of its creator. Once it has emerged, an invention spreads among others by imitation, as Tarde calls it. This term must be understood in the broadest sense, starting from the reproduction of the cultural asset itself (or the reproduction of the method, using this property, of satisfying a given need), all the way to “sympathetic imitation”, i.e. submission to an established norm, adoption of some proposition assumed to be the truth, or admiration for the merit of a work.

During the imitation process, one innovation may conflict and enter into opposition with another innovation; or with a previously recognized cultural asset, in which case a struggle for primacy (Tarde’s duel logique), resulting in one value displacing the other. Only by overcoming all these obstacles and spreading through imitation to the whole of society does an invention become a fact of social life, a cultural element. The culture at any given moment comprises the sum of all inventions that have gotten recognition from the current and previous generations of a people. The life and development of a culture, therefore, can essentially be reduced to two basic processes: invention and propagation. A third process, not required but almost unavoidable, is the duel logique (“logical duel” or struggle for recognition). It is not difficult to see that the two main processes have something else in common: since every invention is inspired by previous inventions or, rather, existing cultural assets, it can be thought of as a combined imitation or, in Tarde’s words, a collision in the individual consciousness of two or more imitative waves (ondes imitatives). The only difference is that in invention there is no struggle (duel logique), in the narrow sense of the word, between the two colliding values. One value does not displace the other. On the contrary, they are synthesized and united into a single whole. Propagation, on the other hand, does not create a new value, but merely eliminates one of the opposing sides. Therefore, invention and propagation can be seen as two sides of the same process, namely imitation. This is what distinguishes Tarde’s teachings – he accepts only one element of social life, the mental process of imitation, always taking place in the individual brain but at the same time establishing a connection between the single individual and other people and belonging, therefore, not to individual psychology, but to interpsychology or collective mentality.