Reconstructing Kenmore, 1890

23 April 2018

I wrote this short essay for a class called “History of Cartography”. Prof. Danzer thought I did a good job, so I decided to share it here.

The area of modern-day Boston between Massachusetts Avenue and Kenmore Square has no common name, despite being one of the city’s most important transport nodes. Beacon Street, Commonwealth Avenue, Massachusetts Avenue, the Mass Turnpike and MBTA all converge here, in addition to the Bowker Overpass—these 50 acres handle virtually all Boston’s long-distance east-west traffic. Fenway Park, Boston University and MIT surround this anonymous, drive-through section of town, which today contains a mix of old and new, residential and commercial buildings. We’ll call this place Kenmore, after the square.

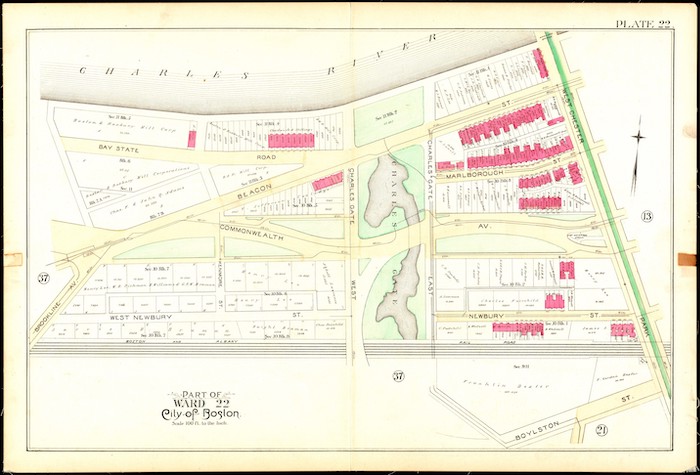

Kenmore wasn’t always a bustling crossroads. “Plate 22” of an 1890 Boston real estate atlas shows that even as late as the turn of the 20th century, this area was sparsely developed. Though carefully divided into lots, most of the map is white, indicating a lack of buildings. This is unlike the other 1890 Boston plates, which feature a dazzling mix of yellow and pink pigment (wood and brick buildings, respectively). The reason for this lack of development is the swampy nature of the land here. The green area of the map labelled “Charles Gate”, along with the unnamed, amorphous pond contained therein, represents the last of the Back Bay swamps that had yet to be filled in. Kenmore’s lack of development, then, is unsurprising—the area on the map had only recently been transformed from useless swamp to stable, buildable soil. More evidence for this is given by the fact that several streets, such as West Newbury and Charles Gate, weren’t even paved yet (not marked in beige). So we can imagine 1890s Kenmore as a sort of urban prairie, with occasional, lonely townhouses lining otherwise mostly empty streets.

The buildings that did exist were brick, as shown by the abundance of pink. Some streetcar lines had been laid already, in anticipation of future development. The Boston and Albany Railroad, with its five tracks, created a southern border for the neighborhood. Nowadays these rails, along with properties on Newbury Street, have been swallowed up by the Turnpike. The main thoroughfare, Commonwealth Avenue, is shown on the map going west-to-east in an undulating, serpentine fashion. This snaking pattern allowed for aesthetic gardens to be placed in the Avenue’s “oxbows”, but surely became impractical in the days of the automobile. Indeed, today’s Commonwealth Avenue has two straight carriageways, with a green in the middle. These deliberate large-scale projects showed that Boston city planners had grand visions for the development of the humble Kenmore area.

What about Kenmore’s human geography? As mentioned above, at this time there weren’t many humans in Kenmore, compared with other parts of Boston. The names of property owners, however, offer insight into the social structure of the area. Virtually every name shown on the map is of British, especially English, origin: Gill, Fairchild, Dexter, Whitwell, Lee, Forbes, Lowell, etc. The only exception is the Braman family, New York-based financiers of Jewish origin. Freeman and Newman are possibly Jewish as well. This contrasts strongly with plates of more central areas of Boston, as well as plates from later years, which feature many Italian and non-aristocratic Irish names as a consequence of massive immigration. Thus we see the nature of property ownership in this new area of the city—it is heavily dominated by elite businessmen, many of whom did not even reside in Boston. This, too, is a testament to the rapid, large-scale growth of Kenmore at the turn of the 20th century, in the manner of modern real estate developments.

Despite its humble beginnings, the Kenmore area was geographically destined to become an important part of Boston. Plate 22 shows us that in 1890, all the makings of a building boom were in place. With the marshes filled, developers were beginning to colonize this newly reclaimed area, spurring the growth that made Kenmore into the crossroads it is today.